Vanna White Couldn't Hit the Legal Jackpot Against New York Lottery, Could She?

/In 1993, Vanna White won a California case against Samsung that many lawyers and judges found preposterous: she won more than $400,000 for a "right of publicity" claim in which she argued that a commercial that featured a robot with a blonde wig turning letters on a board was infringing her likeness. Yes, apparently, in California, she was entitled to more than a quarter of a million dollars because, unlike New York, California has a "common law" right of publicity, in addition to actual statutes that elucidate this right.

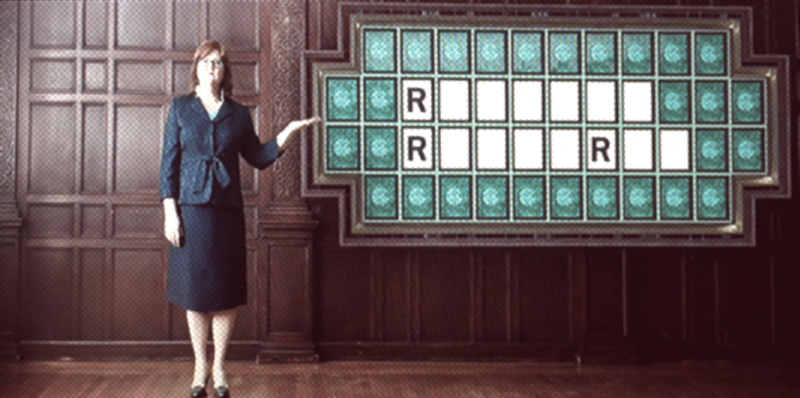

This week, New York Lottery has been featuring a funny ad for the "Wheel of Fortune" scratch-off that takes place during an estate settlement meeting in a lawyer's office. The attorney gives each family member the opportunity to guess the recipient of the decedent's money, by picking a letter. Each family member guesses his or her name as the answer, but the answer is "Reptile Research." Notably, the woman turning the letters is not Vanna White, but a redhead in a blue dress. I immediately thought of White v. Samsung, and wondered if there was even an agreement between the producers of "Wheel of Fortune" to allow them to use another woman to play the letter turner. I would think she would want to hold on to her right to be synonymous with letter-turning hostess, correct?

The redheaded woman featured in the ad looked nothing like Vanna (note: I can't find the video anywhere on the Internet, so I have included a screenshot to illustrate the difference between Vanna and the actress in the lottery ad); of course, a robot in 1993 with a blonde wig did not exactly resemble Vanna, either. If the New York Lottery licensees, in concert with the Wheel of Fortune licencors, actually wanted to protect themselves from a reprise of White v. Samsung in New York, they could have had a man turn the letters. But even if there is no contract protecting the producers of the "Wheel of Fortune" brand, Vanna would not likely have a leg to stand on.

In New York, there is no common law right of publicity, and the concept of the right of publicity is not governed by federal (across all states) intellectual property laws. Instead, each state has its own approach. In New York, right of publicity falls under the concept of "right of privacy," protected by New York Civil Rights Law, Article 5, Section 50:

A person, firm or corporation that uses for advertising purposes, or for the purposes of trade, the name, portrait or picture of any living person without having first obtained the written consent of such person, or if a minor of his or her parent or guardian, is guilty of a misdemeanor.

The much longer New York Civil Rights Law, Section 51 explains the requirements for finding a civil (worthy of private lawsuit) violation a "right of privacy." Names of living people (not companies), portraits, pictures, and voices are protected. It would be hard for Vanna to argue that the commercial used any of these.

While New York is not the haven for celebrities that California is, I find it surprising that celebrities were unable to push for a stronger ability to protect their own likenesses in New York. Perhaps celebrities and their heirs know that, in an era of instant interstate commerce, they can easily wield a greater monopoly over their own identity (and identifiable traits)--even decades after their own death--outside Gotham. I find myself in agreement with Judge Kosinsky's dissent in White v. Samsung:

"Overprotecting intellectual property is as harmful as underprotecting it. Creativity is impossible without a rich public domain. Nothing today, likely nothing since we tamed fire, is genuinely new: Culture, like science and technology, grows by accretion, each new creator building on the works of those who came before. Overprotection stifles the very creative forces it's supposed to nurture."